Automated Chaos: A Brief Overview of Fuzzing

What is fuzzing, really?

Note: Fuzzing inputs are only random sometimes, but they are BS most of the time.

Fuzzing or fuzz testing involves bombarding a program with irregular inputs to uncover potential bugs and vulnerabilities.

Let’s try to further understand this by looking at some of the—

Fuzzing Methods

Whitebox fuzzing:

- Whitebox fuzzing involves fuzzing a program with complete access to its source code.

- Feedback is measured by modifying the source code during the compilation of the program (But we’ll get into that later)

Fuzzing tools suited for whitebox testing: AFLPlusPlus, libFuzzer, Honggfuzz, python-afl

Greybox Fuzzing

- In this method, the tester has limited knowledge of the application, like function prototypes or the decompiled code.

- This approach can be useful for fuzzing closed-source libraries with API documentation that’s readily accessible.

- For example: Microsoft Windows API

Fuzzing tools suited for greybox testing: syzkaller, Hopper, aflnet, aflgo, boofuzz, AFLPlusPlus

Blackbox Fuzzing

- If you have just the binary file of the program and no source code, this method is your best bet.

- Sometimes you might have to use emulation tools like Qemu or Unicorn to run binary files belonging to a different architecture.

- Feedback in this case is measured via binary instrumentation.

Fuzzing tools suited for blackbox testing: radamsa, winafl, Peach Fuzzer, AFLPlusPlus

Pitch-Blackbox Fuzzing

- Okay, so I got a little creative here and just made this term up. But by ‘pitch-black’ I mean programs that cannot be emulated. This distinction becomes important when it comes to dynamic analysis like fuzzing, where you actually have to run the program.

- For example: Embedded firmware designed to interact with specific hardware components.

- This is sometimes known as the

re-hosting problem[ 5 ]. It’s quite a major problem and there’s very limited work done in this field [ 2, 3, 4 ].

Fuzzing tools suited for pitch-blackbox testing: 🌵🌀

Note: Firmwire is an exception, but I’m not familiar with any other fuzzing tools like this. Discord me if you know something I don’t.

But what is feedback?

We need to somehow measure the efficacy of a fuzzing test. For that, we need to get some kind of ‘feedback’ from the process while it’s being fuzzed.

The fuzzer could also then leverage the feedback obtained from the target process and adapt its input generation.

Feedback is usually measured using various metrics such as: 1) Code Coverage: This is the most important form of feedback. It measures the extent to which the source code of a program has been executed during the testing process

2) Edge Coverage: Even 100% code coverage does not guarantee effective testing. As such, measurement of the transitions between basic blocks in the control flow graph of the program can also provide useful insight during fuzzing.

3) Memory Usage: It can also be useful to keep track of how the target application allocates and deallocates memory during the execution of test cases. Generating inputs that lead to frequent memory allocations is an effective way of uncovering new bugs.

4) Input Validation: It might be helpful for the fuzzer to know whether the input being supplied to the target process is valid.

Note: The terms “feedback-driven” and “coverage-guided” are frequently used interchangeably, but they are not necessarily the same. Feedback-driven fuzzing is a broader term that encompasses coverage-guided fuzzing.

Coverage Tools

afl-plot: Useful for generating graphical representations of AFL’s performance and coverage data.

afl-cov: Provides code coverage information collected during the fuzzing campaign

Code Coverage visualizers

VSCode

Instrumentation

Instrumentation is the process of injecting additional code into a program to collect data about its runtime or to modify the program’s behavior.

Source Code Instrumentation:

Fuzzers can instrument the source code to collect coverage information by directly modifying it to add additional code during compilation. AFL enables source code instrumentation by integrating with other compilers.

1

afl-gcc fuzz.c -o fuzz

AFL can also use the LLVM compiler to insert instrumentation code using LLVM passes

1

afl-clang-lto fuzz.c -o fuzz

Binary Instrumentation:

Binary instrumentation, as the name suggests, involves modifying the compiled binary code of a program to insert additional instructions.

For instance, you can use dynamic instrumentation toolkits like Frida to inject JavaScript or native code into running processes or intercept and modify function calls.

Note: It might be possible to contrive a pretty interesting coverage-guided fuzzer using Frida, but I’m not sure how well it would perform. To my knowledge, I don’t think anyone has done this.

Input Seed Generation: Where Fuzzing Begins to Sprout

The initial set of seed inputs in the corpus serves as a starting point for the fuzzer. These seeds are typically valid inputs that help the fuzzer understand the structure and expected format of input data.

Aim for diversity in the input corpora(that’s the plural form of corpus 🤓) to increase the chances of discovering a wide range of vulnerabilities.

Alternatively, one could also leverage the test suites and example usage often included in the source code repository.

Mutations

Mutation-based fuzzing is a technique where new test inputs are generated by tweaking existing inputs.

In the case of feedback-driven fuzzing, the feedback information is used to guide further mutations. Inputs that lead to new or uncovered code paths are considered interesting and may be prioritized for further mutation.

Mutation techniques:

Random

This involves aggressive and chaotic mutations of the input data like:

- Random bit/byte flipping

- Deterministic arithmetics

- Splicing (Combining two inputs from the queue)

- Overwriting the input with interesting 8, 16, and 32-bit values

Lexical

For higher code coverage, it’s beneficial for the input data to contain certain “interesting” characters or tokens.

State-of-the-art fuzzers, will analyze comparison operations to extract such interesting constants that enable the fuzzer to generate input data that can explore more branches.

Examples:

if (strcmp(header.magic_password, “h4ck3d by p1gZ”)) goto terminate_now;

if (header.magic_value == 0x12345678) goto terminate_now;

This method by itself can be extremely powerful, such as mutating a string into valid JPEG images.

You could also further enhance this by making use of AFL Dictionaries by generating a set of valid inputs to guide the mutation process.

Lexical mutations involve modifying the input data while taking into account these special values.

Syntactic

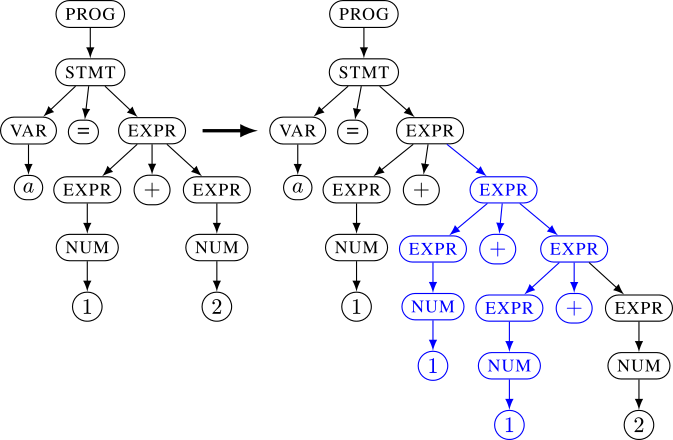

This is useful for fuzzing programs that require highly structured inputs such as interpreters and compilers[ 6 ]. Additionally, you can think of this as feeding the target program input data that can find crashes “deeper” in the program.

Source: https://github.com/nautilus-fuzz/nautilus/tree/master

Grammar-aware fuzzing is usually done by providing the fuzzer with a grammar file. [ 7, 8, 9 ]

Nautilus also allows you to specify a script rule along with the grammar file.

One interesting use case for this is to generate a valid Message Authentication Code (MAC) of the input data created by the fuzzer.

1

2

3

4

# Grammar rule for HEADER

# Grammar rule for BODY

ctx.script("MIME", ["HEADER", "BODY"], lambda header, body, hashlib=__import__('hashlib'):"{}\nX-MAC:{}\n\n{}".format(header.decode("utf-8"), hashlib.sha256(header + b'\n\n' + body).hexdigest(), body.decode("utf-8")))

This script will generate a sha256 hash of the MIME header and body generated by the fuzzer, and then it will append the X-MAC header before sending the input to the target program.

This is useful since the target program may simply discard the input data generated by the fuzzer if the MAC is invalid, resulting in limited coverage.

Note: The grammar file doesn’t have to be comprehensive for fuzzing purposes. But exactly how much “structure” one should provide to find the most bugs is an interesting question. (Again, if you know something about this, here’s my Discord)

Semantic

Semantic mutations require an understanding of the underlying semantics program’s API, such as the s function signatures and type definitions [ 10 ].

Note: AFL doesn’t really fall into any one category because it allows you to write your own custom mutators.

Additional Note: Take this part with a grain of salt. This is my attempt at broadly categorizing all the mutation techniques.

Crash Back Guarantee (Santizers)

AddressSanitizer (ASAN) is a memory error detector tool designed to dynamically find memory-related bugs. It was developed by Google as an open-source project and has now become a part of the LLVM infrastructure.

ASAN works by instrumenting the target program during compilation to inject code that monitors its memory operations.

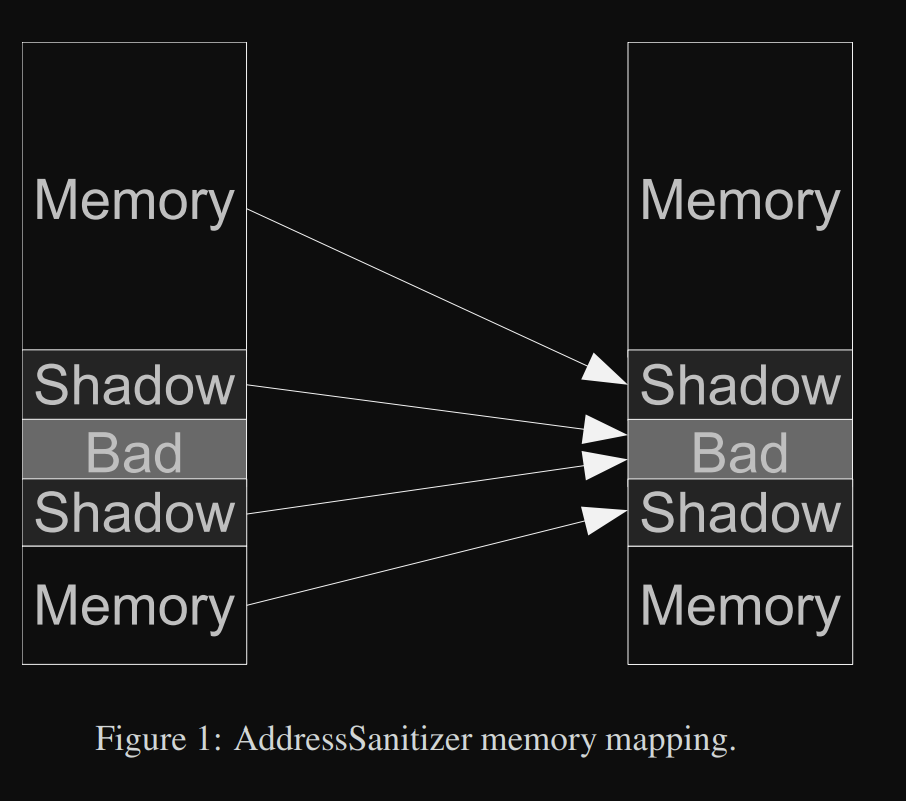

ASAN works by mapping the entire memory address of the program to a data structure known as the shadow memory. When memory operations occur in the target program, the instrumented code reflects this in the shadow memory.

All memory checks are then performed on this shadow memory.

If the shadow byte signifies that the associated memory falls within the valid allocation bounds, the operation continues as usual.

Source: https://storage.googleapis.com/pub-tools-public-publication-data/pdf/37752.pdf

Note: Other sanitizers that may be of interest: https://github.com/google/sanitizers

Pitfalls and Side-Effects:

IO:

The fuzzer may generate a large number of input test cases. Along with this, the fuzzer may also read and write to these test cases to mutate them. This leads to intensive Input/Output (IO) operations on the storage device. Depending on your filesystem and how long you run the fuzzer, this may have adverse consequences.

This blog post I found compares the effects of fuzzers on various filesystems.

TLDR: RAM file systems are the safest option. Tmpfs is slightly better than ramfs because it does not grow dynamically.

AFL supports this via the AFL_TMPDIR environment variable.

Syscalls

If you have access to the source code, you may want to eliminate any potentially harmful syscalls, as you never know how the program is going to behave while being fuzzed. Additionaly, if you have just the binary file, you can make use of custom preload libraries such as preeny to dynamically change the behavior of the syscalls.

Other reasons to edit syscalls may include:

- Redirecting socket IO to the console

- Disabling forking

- Disabling rand() and random()

- Redirecting file IO

Most of these problems are fixed by containerization .

Example:

1

2

3

4

5

docker pull aflplusplus/aflplusplus

docker run -ti -v ~/src-dir:/src --memory=1024m \

--mount type=tmpfs,destination=/ramdisk -e \

AFL_TMPDIR=/ramdisk aflplusplus/aflplusplus

Note: I added the ‘–memory’ tag to impose a constraint on memory usage.

Some additional references

https://github.com/antonio-morales/Fuzzing101

https://j00ru.vexillium.org/slides/2016/blackhat.pdf

https://www.fuzzingbook.org/

https://moyix.blogspot.com/2016/07/fuzzing-with-afl-is-an-art.html

https://lcamtuf.blogspot.com/2015/04/finding-bugs-in-sqlite-easy-way.html

https://blog.attify.com/fuzzing-iot-devices-part-1/

https://users.cs.utah.edu/~snagy/courses/cs5963/schedule

https://github.com/parikhakshat/autoharness